How can we help kids be more creative? It’s a question I often think about when working with students at Garden Street Academy. Creative thinkers make better problem-solvers. Here’s a bit of insight I recently had with sixth graders in my 3D printing and design class.

I’m teaching them to design for our 3D printers using Tinkercad. It’s a simple online tool that students use to build objects by assembling primitive shapes like cubes, spheres, and cones. Tinkercad provides six short tutorial projects that quickly get students up to speed.

Since the tutorials aren’t very inspiring, I needed another way to spark my students’ creative fires. After they finished, I gave them their first challenge: create an abstract sculpture. I wanted them to feel unconstrained; that they could make anything they could dream up.

It’s harder than it sounds, actually. If you tell students to “just make something,” you risk many of them sitting idle trying to think of an idea. I needed a catalyst to show them what’s possible. I showed photos of large format sculptures like David Smith’s Cubi XX and the Eduardo Chillida’s Elogio del Horizonte. These sculptures are relatively simple. They are more or less composed of the same primitives available in Tinkercad.

Still, I didn’t give my students a whole lot of direction, and that’s part of the challenge. Can they overcome the initial hurdle of just starting something, anything? Can they just begin (ala Mark Watney)?

So, they began. But after a short while, one of my students seemed to be stuck and asked, “How do I make an ice cream cone abstract?”

I froze for a second. I didn’t have an immediate answer. I hadn’t thought about it before. Cool!

Working through the creative process

I directed the class to stop what they were doing and gather in the middle of the tech lab. I asked them what they thought abstract meant. They talked about concepts like weird, “out there,” different, unusual.

“What is an ice cream cone?” I asked. A few quizzical looks ensued. “What shapes is it made of? Think about the primitive shapes in Tinkercad.”

Lightbulbs.

“A cone and half a sphere,” they said. Right!

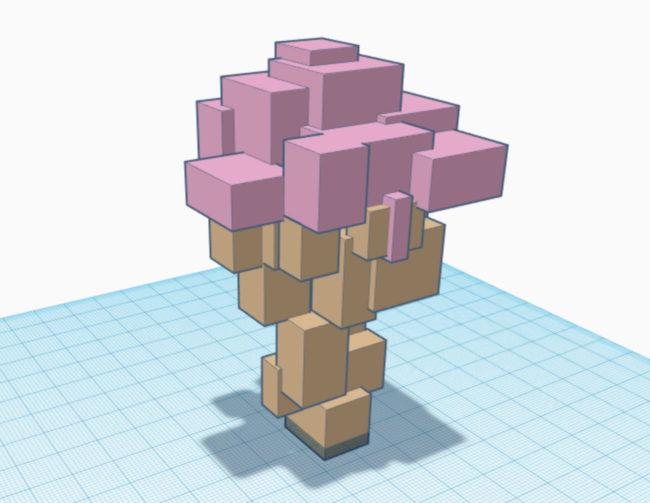

Okay, so how do you take a simple shape and make it different and unusual? This is when Minecraft flashed in my head, and I thought about its blockiness.

Reinventing a cone

I asked the class, “What if we made a cone out of blocks?” Then I quickly dragged a bunch of cubes onto the workplane. I randomly resized and arranged them up into the shape of a cone.

Quick Sidebar:

Ideally, I prefer to ask leading questions to help students discover a concept like this on their own. I would rather not offer a solution outright, but time was short, and I quickly wanted to get them back to designing their sculptures. I intervened earlier than I might have otherwise.

Now we had a cone that was weird and “out there.”

So what just happened? How could help them learn to be more creative?

Imposed a constraint – I limited myself to a single shape that was completely different from a cone. That showed my students how to change their perspective and think differently. Developing this skill helps them come up with new ways to attack problems.

Complexity and interest – I gave every block has a unique size and shape. I also felt free to place each of the blocks with more thought and artistic intent. The abstract cone is one of a kind and much more interesting than Tinkercad’s primitive cone. Even more creative decisions open up when you think about whether the middle of the cone gets filled. Should there be air gaps between each block?

No perfection necessary – I created the original cone in about three minutes. I had to be fast to keep my students engaged. That meant I didn’t have time to obsess about sizing and positioning each block. I just had to do it. This is essential because striving for perfection can destroy creativity. I didn’t fixate on minor details and still got a decent result.

Permission to be different – Another important outcome of my demo is that it permitted my students to be different. With an “abstract sculpture,” there’s no wrong answer. The fear of negative judgment evaporates. When students feel safe to take risks, their creativity blossoms.

How did they turn out?

The students made some amazing art, especially for their first creative designs in Tinkercad. I love that none of them tried to be literal with their sculptures. Some resemble animals but deviate in interesting ways. Others are more architectural. They look like they might have been early ideas for Patch Adams’ Gesundheit! Institute.

Here’s a 3D version of their models shared from Tinkercad. You can zoom into and rotate around their models to see more details.

And the student who asked how to abstractify (my word) an ice cream cone? That student’s sculpture is the second one from the left in the front row. The title of it was “Pig.” I love that! They still used a cone in the sculpture but went with an idea different from an ice cream cone.

Tie it all together

Creativity has to be spontaneous, almost instinctual. If students start to overthink, they’ll fall into the analysis-paralysis trap, and their creativity grinds to a halt.

Don’t get me wrong. Critical analysis has its place, just not in the brainstorming phase. Perfecting a creation should only happen at the end of a project after all the main ideas have been fleshed out.

If your kids or students are stuck during a project, get them moving or doing something, anything. If they’re not writing, get them to write nonsense. If they’re not painting, give them a used canvas and tell them to paint the opposite of what they are trying to paint. If all else fails, have them take a short walk, with no electronic devices.

Activity sparks creativity.

How do you inspire creativity in your students? Share your story in the comments.